- Home

- David Abbott

The Upright Piano Player

The Upright Piano Player Read online

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. The author’s use of names of actual persons, places, and characters are incidental to the plot, and are not intended to change the entirely fictional character of the work.

Copyright © 2010 by David Abbott

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in Great Britain by MacLehose Press, an imprint of Quercus, London, in 2010. Published by arrangement with Quercus Publishing PLL (UK).

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Liveright Publishing Corporation for permission to reprint an excerpt from “i will cultivate within” by E. E. Cummings, copyright © 1931, 1959, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. From Complete Poems: 1904–1962 by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage, copyright © 1979 by George James Firmage.

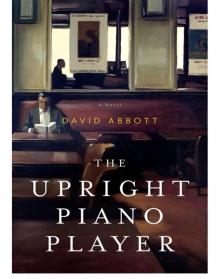

Cover painting: Rue des Boutiques Obscures–Scene 1, by Denis Frémond. Private collection. Jacket design by Emily Mahon

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Abbott, David, 1939–

The upright piano player/David Abbott.—1st American ed.

p. cm.

1. Retired executives—Fiction. 2. Stalkers—Fiction.

3. Stalking—Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PR6101.B35U67 2011

823′.92—dc22

2010038869

eISBN: 978-0-385-53443-7

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Part One

Part Two

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Acknowledgments

About the Author

The consequences of our actions take hold of us, quite indifferent to our claim that meanwhile we have improved.

—Nietzsche

the snow doesn’t give a soft white damn Whom it touches.

—E.E. Cummings

Part

One

NORFOLK | MAY 2004

He knew it was unforgivable to drive to the funeral in the old Land Rover, but it was the only transport he had. And anyhow, what difference did it make? What did any of it matter now? The day the police had returned the car he had taken it to the local dealer and they had ripped out the old seat belts and fitted the modern, retractable kind. They had done it in a few hours as an act of kindness, but to him the quick turnaround had felt more like a reproach.

He was not expected at the church. He had told his son that he was not up to it and could not come. That morning, he had found he could not stay away either, and had shaved in a hurry, cutting himself on the neck so that the collar of his white shirt had picked up specks of blood as he fumbled with his tie. A week ago, the doctor had given him sleeping pills, but he did not want oblivion and had not taken them. Now his eyes were almost closed, like those of a boxer at the wrong end of a good left jab, and driving to the church he had strayed onto the verge and mown down fifty yards of cow parsley before regaining the road. Following the arrows chalked on the gateposts, he parked in the meadow next to the church. The sun was high in the sky and the number of red cars in the field depressed him further.

As he walked into the lane he listened for music. There had to be music. It had been a bond between them. Favorite tapes played over and over in the car, a phrase in the lyrics or an exuberant riff prompting delighted laughter, always on cue. He hoped someone had thought about the music—chosen something suitable, not too religious. He would have done it himself—would have done it better than anyone—but they had spared him the task. Get some rest, they had said. Rest?

That night, in the small hours, he had consulted his battered copy of Hymns Ancient & Modern. In the index, trying to second-guess his son, he had looked through the list of hymns for special occasions, but he had found evidence only of the Victorians’ preoccupation with sin and self-improvement. There were hymns for a temperance meeting; hymns for a teachers’ meeting; hymns for the laying of a church foundation stone—but he could find no recommended send-off for a small child dangled from a moving Land Rover.

The church door was closed, but through the open windows he heard the ebb and flow of a prayer and knew that it was too late to go in. He imagined the creak of the door and the click of his heels on the flagged floor, the heads of the congregation scrupulously not turning.

He walked down the path towards the newly dug grave. The grass matting draped over its sides reminded him of displays in garden centers, overly emphatic in this place of tired turf and ancient stone. The grave’s opening seemed almost jocular, little more than a slot in the soil. But then the replays started running in his head and he was sitting on the sofa with his arm around the boy’s narrow shoulders and he knew there had been no mistake.

Dear brain, please stop, he pleaded.

He looked around for distraction. The surrounding gravestones bore the name of his daughter-in-law’s family. In the next plot, leaning protectively towards the new grave, was the headstone of John and Clara Burnham, the boy’s maternal great-grandparents. In a hundred years’ time, visitors to this church might wonder how an eight-year-old boy named Cage came to rest here among the long-lived Burnhams.

Then he heard it.

From the church, came the familiar sound of a cha-cha-cha. One night at supper, they had all agreed that Ruben González was the best musician in Cuba. He saw once more the boy slip down from his chair and jig around the kitchen, arms held high, dark hair flying, the back of his head so perfect. He felt ashamed of his worries about the music. Why had he doubted that his son would get it right? God knows, no one was closer to the boy; no one loved him more. Not even me, he thought, and I loved him mightily.

The church door opened and he stepped back from the grave. He did not want a place in the front row and retreated to the cover of the blackthorns by the churchyard wall. Two men carried the small coffin on their shoulders while the last chorus of La Engañadora spilled out from the church. He realized that his foot was beating time. He stopped it, reassured that no one could have seen its movement in the long grass. How difficu

lt it must be for the bearers to maintain that slow, measured tread when the music demanded a wilder gait.

Out from the porch came his son and daughter-in-law. She was holding Beth, now two and his only grandchild. Behind them were her parents and her three sisters with husbands, partners, and children clustered around them. He knew the Burnhams would overcome this loss, draw together and consolidate. Through the trees he could see the roof tiles of their family home—the house a mere fifty yards from the church, snug in the fold where the lane dips down into the valley. His grandson’s grave would be well tended. The Burnham side of the family would not let the boy down.

As the mourners gathered around the grave, his son saw him. There was a small smile of recognition, but no attempt to wave him closer. He stood for a while, not really hearing, not really seeing, and then slipped away through the side gate and back to the car. They had planned a buffet lunch at the Burnhams’ after the service, but he would skip that. He could not meet people right now. He sat in the car and closed his eyes. He would rest before driving home.

There was a rap at the window.

“Dad, open the door.”

He stirred, almost asleep.

“I’ve come to get you. You must come.”

His son’s dear face was the other side of the glass, only inches away. He looked ill, terminally so. Well, he was in a way, wasn’t he? Don’t they say you never recover from the death of a child? He opened the window and shook his head.

“I can’t go in.”

“Dad, I need you there.”

“Ah, no.”

“I need them to know that I haven’t lost you as well.”

The Burnhams’ house was handsome. A white stucco façade, Dutch gables, and the windows and doors arranged with a pleasing symmetry. The sun had shifted, so that the windows of the crowded drawing room were in its full glare. Uncomfortably hot, Henry sat on a low chair that had been brought down from the nursery as emergency seating. He waited patiently for it all to be over. His head was at hip level to the crowd and as long as he did not look up no one could catch his eye. From time to time, someone patted him on the shoulder and moved on. Two pats were the most common form of sympathetic currency. The vicar had given him just one, but he had left his hand there for a beat longer than anyone else, and there had been the hint of a squeeze. Not knowing what to say, people had said nothing.

He must have nodded off for he was surprised to feel his son’s hand cupping his elbow and helping him to his feet.

“Come into the kitchen, Dad, it’s quieter there.”

He was led to a wing-backed chair by the stove. The cushions yielded to his shape and he closed his eyes. It was three o’clock in the afternoon. He slept for six hours. When he awoke, he saw white plates stacked in columns on the kitchen table and rows of gleaming glasses. The room was tidy and clean. They must have been clearing up around him, talking in whispers, if talking at all. When he stood up he had to hang on to the chair for support. These days, his left knee had a tendency to seize up if not flexed at regular intervals. He aimed a few kicks at an imaginary ball and was able to stand unaided. The kitchen was almost dark, the only light coming from a small lamp on the dresser. They had obviously wanted him to sleep. Their consideration seemed inappropriate.

“Oh, you’re ready.”

His son came into the room.

“We’re taking Beth home now. We can go by yours, if you want.”

“No, I’ve had a sleep. I can get myself home.”

His son was suddenly in his arms.

“It was an accident, Dad—an accident.”

Henry did not answer, but held him tight. There was the smell of wood smoke in his son’s hair and clothes. The family must have lit the fire in the front room, not for the warmth, he thought, but because on a day like this it would be unbearable to contemplate an empty grate. He kissed the soft skin at his son’s temple and let him go.

He was still in his suit, sitting in an armchair, when the phone rang. He knew what time it was for he had been awake listening to the radio—more mumbo jumbo about the reconstruction of Iraq. It was 4:00 a.m., but he was not surprised to get a call. He was slow getting out of the chair and trod on his book as he made his way to the phone. He supposed it would be his son.

He recognized the voice of his daughter-in-law.

“I didn’t wake you?”

“No, you didn’t wake me.”

“I’m glad. I don’t want you to be sleeping when I’m not.”

Before he could answer she had replaced the receiver. At last, blame had been apportioned. It was the first time she had spoken to him since the death of her son.

“Have a good time. Don’t get your feet wet!”

She had been at the front door crying out as they left. He had driven over to collect the boy for an outing. They were going to the wild fowl sanctuary to take photographs. His grandson had a good eye and was patient. He could sit motionless in the reeds for an hour if necessary. It was odd really. In the house he was a fidget like most small boys, but at the lake he grew up. They were both competitive and had turned the trips into a contest. The game was that they each had five shots, taken in turns on the same camera. Back home, he transferred the pictures onto his computer and the boy’s parents would later pick out the winner. More often than not, it was one of the boy’s photographs that won.

The bird sanctuary was only fifteen miles away and even at the weekends the roads were rarely busy. They never hurried—the car was not up to it, for one thing, but more than that they valued the time they had to talk. Once at the lake, it would be hurried whispers and sign language.

That afternoon, he had a good tale to tell.

“What is it, Grandpa, what happened?”

“This is one of my true stories, all right?”

The boy had smiled.

“Well, you know how early I get up? This morning I went for the newspaper, same as usual, nobody around. On the way back, just after the humpback bridge, where I start to slow down for the left-hand turn, that’s where I saw it.”

He had hesitated and looked across at the boy, who had simply raised his eyebrows, old enough at eight to indulge a dramatic pause.

“It was a barn owl. It came up from the field and started flying alongside the car. I had the window down and the owl was no more than four feet from me at eye level. It was keeping pace with the car and, I promise you, it was staring at me all the way—as if I was a tasty field mouse.”

He had been rewarded with a giggle.

“I was doing twenty miles per hour and he stayed with me for two hundred yards, right until the turning, barely moving his wings to keep up.”

There was more he could have said. He could have said it had felt like a blessing. That he had marveled at the bird’s face—in close-up even flatter than you imagine, like a cartoon bird that has flown into a wall. It had seemed a gift. Like the sighting of a kingfisher, a singling out, a portent of favor.

How wrong can a man be?

He made himself some coffee. There were already three full mugs on the draining board. They must have been there a long time, for a skin of dust had turned the black surface gray. He put the fresh cup alongside them and opened the back door into the garden. The night air was cold so he closed the door. Such is the banality of grief: the endless repetition of pointless activity. For two weeks he had walked the internal boundaries of his house, opening and closing windows, checking cupboards, peering into the empty fridge, climbing the stairs and wondering why. Even music had failed to bring relief. Every so often he would sit at the piano, but could never bring himself to play. Late in the day, fatigue would overcome his restlessness and force him into a chair, where he would sit waiting for sleep. Now with the confirmation of his guilt, that phase was over. He went back into the drawing room and took down the bottle of sleeping pills from the mantelpiece. Let’s try oblivion, he thought.

He awoke hours later. His mouth was dry and his first conscious thought

was of the boy and the sequence he was trying to erase from his head. Slowly the sound filtered through, a domestic duet of running water and the clink of dishes. Someone was downstairs. His front door was never locked. It had been a point of principle when he moved up from London, one of the reasons for coming. He had wanted to believe that what had happened to him in London had been a big-city aberration; that here on the road to nowhere, the old certainties were still in place, that you could leave your house and car doors open and suffer no ill. He had been warned that it was no longer so and that his romanticism could be dangerous.

On the road to the lake they had pulled in at Barton’s petrol station. It was one of the few independents left and its two pumps were seldom used. Locals and tourists alike preferred the facilities and lower prices of the Shell garage three miles on at the roundabout. Old man Barton had converted his redundant servicing bays into a mini-market and did a fair trade. It was a place where you could buy canned goods and jumbo packs of frozen chips, binding twine, shoe polish, a bag of coal, bread, newspapers, and, in season, fruit, vegetables, and flowers from the neighboring farms and gardens. The produce was displayed on tables outside and there was usually someone looking it over.

The Upright Piano Player

The Upright Piano Player