- Home

- David Abbott

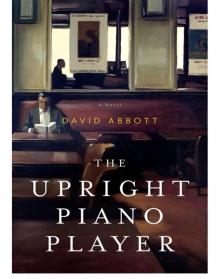

The Upright Piano Player Page 4

The Upright Piano Player Read online

Page 4

There was a message on his answering machine. He was invited to watch the fireworks from a friend’s riverside flat near Southwark Bridge. Nothing special, anytime after 11:00, bring a bottle.

He was fortunate to find a cabbie on the Kings Road willing to take him as near as possible to Upper Thames Street.

“Won’t be easy, they’ve closed everything off. We’ll have to go round the houses. Might be able to get you as far as Mansion House tube station?”

There were already thousands of people on the streets at 10:30, most of them walking towards the river. His cab headed north, against the tide, and onto the Marylebone Road. Here, the traffic was sparse and fast flowing. Only at the traffic lights would you have known that it was a special night. Car windows were lowered as the habitual race to be first away was suspended and drivers found time to exchange greetings. A minibus drew up alongside Henry’s cab. The passengers in the back were already merry and one of them dropped an empty whiskey bottle out of the window.

“Happy fucking new century,” they chanted.

Henry sank further into his seat, anxious not to catch anyone’s eye.

The crowds thickened as they approached London Wall and the cab driver finally lost his sense of adventure. As he drove off, Henry remembered his umbrella on the backseat. Rain had been forecast for about midnight. He joined the throng walking purposefully towards the river. It was at this stage a silent march, everyone too earnest for talk, eager to get a clear view of the fireworks and the much heralded, but unimaginable, wall of fire.

The block of flats where his friends lived had been cordoned off by the police. It stood on a narrow alley leading to a short waterfront walkway. He explained that he had an invitation to one of the flats. “Lucky you,” the policeman said, turning his back. Henry was wedged in by the crowd and could only wait for another policeman to come near enough to hear his plea. There was too much noise to shout. To his right, he could see kids climbing over the barriers and sauntering down to the river. The police, casually grouped around their portly motorcycles, didn’t seem to notice. “What about them?” Henry yelled, pointing to the grinning teenagers, certain now of ringside positions. A woman in a white plastic mac tugged at his sleeve. “Don’t worry love, they’re letting us all in at twenty to twelve.”

“I’m sorry to be so late, they’ve only just opened the barriers.”

“It’s no problem—you’re here, that’s the main thing—and in time for the big bang, too.”

Henry handed over his bottle of champagne and received a full glass in return.

“Come and meet everyone. You’ll know many of them.”

William had been one of Henry’s protégés, the brightest of the bright, and Henry’s pick to run the company. Instead, William had decided to start up on his own. Failing to dissuade him, Henry had offered to back him, but William wanting independence had allowed him to take up just 5 percent of the new company. It was enough; the two men, though separated by twenty-five years, were genuinely fond of each other and the business connection had added only spice to the friendship—the existing ties were already secure.

There were about fifteen people in the large interconnecting rooms and perhaps the same number of children, though it was difficult to do a head count of the young as they rushed from room to balcony and back again. There were several people from the company and he embraced them warmly. He saw Grace on the balcony and went out to greet her.

“Oh, you’re here,” she said, “I was worried about you. I know how much you hate humanity en masse and—come and look—it’s rarely more en masse than this.”

She led him to the edge of the balcony. Looking down from the third floor, it was as if someone had lifted the lid of a tube train in the rush hour—people packed so tight that when the rain came later, it would fail to reach the ground.

“Have you seen the boys?”

“Yes, in passing.”

He had been at Grace and William’s wedding. He and Nessa were godparents of their eldest son and he knew, without a shadow of doubt, that Nessa would still be part of the boy’s life.

“Quick, everyone onto the balcony. It’s two minutes to midnight. Bring your glasses.”

A short wait, almost silence, and then the air is rent with rockets, the gray barges disgorging their cargos with synchronized fury. Henry is reminded of newsreel footage of the Gulf War. The bangs are sharp, high on treble, and he would like to have given them a little more bass, but no one else seems bothered. He sees that the adults are like children, their eyes bright and mouths agape, but the kids have moved on and are looking over the railings at the people below. The display lasts for sixteen minutes and is judged to have been wonderful. No one sees the wall of fire. Half an hour later, pleading jet lag, Henry left.

He had been told that the underground station at St. Paul’s would be open, but he couldn’t get close enough to find out. The crowds funneled him against his will into Ludgate Hill and he decided that it was useless to resist. There seemed no alternative but to walk home. It had started raining, a moist, intrusive drizzle. In Fleet Street, the thousands walking west met the thousands walking east. He slowed to a shuffle. For a while, the crowds maintained their good humor. Parents with tired children in pushchairs took refuge in the shop doorways from the rain and the flood of pedestrians. He felt hot, distressed by the body heat of strangers pressed too close and the thick damp wool of his overcoat. As he approached the Aldwych, he stumbled but was kept on his feet by the press of the crowd. He started veering to the left. He wanted to get out of this rat run, to cross Waterloo Bridge and reach the safety of the south bank. Perversely, the bridge had been closed. It seemed crazy to channel people down the Strand towards Trafalgar Square. He stepped over a drunk lying in a bed of broken bottles, the blood on the jagged green glass uncomfortably vivid.

He kept close to the shop fronts, hoping against hope that the alley by the Savoy had not been closed and that he could escape down onto the Embankment. It was open. He sidled into its sanctuary. Fingers crossed, the multitudes would not follow.

The steps took him down to the rear of the hotel and he felt that the worst was over. The gate to the gardens was open and he took a shortcut through the shrubbery. The rain had made the ground treacherous and he slipped, sliding down onto the pavement through a sea of mud. Someone helped him up. The crowds, if anything, were more solid than in the Strand. He felt like a foot soldier at the Somme; his fall had left his coat and shoes khaki with mud. Weary now, he joined the slow march to Westminster Bridge. His plan was to cross Parliament Square and then work his way to Belgravia and on to Chelsea. He looked at his watch. He had been walking for an hour and a half.

As he approached the bridge, youths made unattractive by drink and rain were dancing on a tawdry stage erected in the riverside gardens. The crowds here were impossible, like four football stadiums all letting out at the same time. Henry was frightened—fall now and he might be trampled to death. He started pushing towards the square. A man, just inches from his face said, “Don’t bother, they’ve closed it, we’ve all got to go over the bridge.” Henry turned round and was carried by a surge of the crowd into the back of a young man. The man elbowed him hard in the chest.

“Don’t be silly, I can’t help it—the crowd is pushing me.”

The young man twisted to look at him. The crowd swept Henry forward again and he was tight up against the man’s leather jacket. Henry felt a booted heel smash into his shin.

“Oh, don’t be so infantile”—even as Henry said it, he knew it was the wrong word. The man lowered his head and brought it back hard against the bridge of Henry’s nose. He slumped, head swimming, the pain acute, but he did not fall. The crowd held him upright. There was an illusion of toughness—the man they can’t put down—and then a shift in the crowd and he was on the ground.

“Back off! Back off! Someone is down!”

He was dragged onto the pavement and propped against the balustrade. He was aware

and embarrassed. People stepped over his outstretched legs, not always successfully. He was just another man who had partied too long, the blood on his face the legacy of a drunken fall. He got slowly to his feet and fumbled for a handkerchief. His forehead was bleeding, but his nose did not seem to be broken.

By keeping close to the railings, he made it across the bridge. South of the river the walking was easier. The crowds had thinned and he made good progress along the Albert Embankment. Oncoming pedestrians scuttled out of his way. Later, catching his reflection in a shop window, he understood why. His hair, thickened by rain and mud, was a wild halo above a soiled and bloody face. His clothes were dishevelled. He looked like a vagrant with a grudge.

He had expected to turn north at Lambeth Bridge, but the police had erected yet another barrier. It seemed he had become a competitor in a monstrous obstacle race. He looked over the hurdles at the empty road stretching across the bridge, the first open space he had seen in hours.

“You’ll have to go down to Vauxhall, that’s the only way you’ll get over the river.” A man with a sleeping child heavy in his arms shrugged at the flat tones of the policeman. Henry wanted to ask why was the bridge closed—what logic from above had deemed it necessary to turn celebrants into refugees, to fuck up the first few hours of the new millennium? Newly cautious, he turned away. He did not imagine that policemen did head-butts, but decided not to risk it.

On Vauxhall Bridge he saw the first traffic. He was limping and his head hurt. There were still hundreds of people on the pavements and he walked in the gutter, too tired to cope with the minute changes of direction required up there beyond the curb. When the gutter became too cluttered with debris, he stepped out into the road, ignoring the hoots of the cars and the insults of the drivers. He walked, head down, through Victoria and into Eaton Square. It was 3:30 in the morning and his ordeal was not over. On the Fulham Road, a boy and girl bumped into him. They looked no more than fifteen, cold and pinched in their T-shirts, clutching beer cans to their narrow chests. “Happy New Year,” they shouted. Henry ploughed on, saying nothing, close to home now. They followed him. “Well, fuck you, you wanker. Fuck you!” A beer can hit him in the back as he reached his gate.

4

In Florida, it is hard to find a cautious property developer. Subsidized by the city managers, they fling up shopping malls at breakneck speed, indifferent to the fact that many of the ventures will never cover the city’s costs. The Plaza Delray, however, had been a success; profitable for twenty years, it had only recently shown signs of decline.

The drugstore and the Italian restaurant had closed and only Jack’s Café, with its white plastic tables grouped under the shade of the two large ficus trees, promised conviviality. True, there was sometimes a bustle inside Rita’s Beauty Parlor—and the dry cleaners did a steady trade, pulling in drivers from Ocean Boulevard, but it wasn’t enough to dispel the feeling that the Plaza Delray needed a face-lift.

For Nessa, the developer’s plans had been invigorating. The ficus trees had been plucked out and were replaced by date palms, more in keeping with the Spanish colonial style the architects now desired. The flat gray roof tiles had been supplanted by tiles of chunky terracotta, ribbed and undulating. The plain walls were adorned with fake arches and capped with deep architraves.

Each morning at breakfast, Nessa watched the reconstruction work from one of Jack’s tables now shaded only by the green parasols he had been forced to buy. The work was surprisingly simple; what appeared to be stucco on brick or concrete was, in fact, paint on polystyrene. Blocks of it, two feet wide and six feet long, were cut and molded and then pinned to the walls. Two coats of acrylic wall texture, the first in gray and then in sand, completed the illusion. The Plaza might now have all the integrity of a Hollywood film set, but new leases were being taken up and Phil, the drugstore owner, was coming back.

Jack welcomed this new vitality, but he mourned his trees. He had even considered selling up and going back to New York, but the life here was too comfortable to leave. He played tennis most mornings and in the warm Florida climate his sixty-year-old body got down to low balls on forty-year-old knees. For that alone, you stayed.

“You all right there, hon, you want a refill on that coffee?”

Arlene, the waitress with boyfriend troubles, sashayed round Jack and Nessa as they talked.

“So, when is he coming?”

“He’s thinking about it. But he’ll come—I don’t think he’s got much else to do.”

“Does he know the way things are with you?”

“No, I’ll tell him when he’s here.”

She stood up. “See you tomorrow, Jack.”

He watched her go. They were both unattached and had become friendly when she had returned from England. With a little encouragement, he could have loved her, but she had sweetly deflected his advances and he had settled for what was on offer. They were best friends and dancing partners, nothing more, but that did not stop his pulse quickening every time he saw her.

Her house had been her mother’s, the holiday home of Nessa’s childhood. It was now the last modest dwelling on the Boulevard, a single-story anachronism among the new-money mansions. From the road, it hunkered down in a hollow, so that only the green-tiled roof was visible from the gated entrance. At the back, a wooden deck faced due east. From the deck, a narrow lawn sloped down to the seawall and the beach. Steps had been set into the wall and Nessa walked to the water’s edge. Above her, cormorants cruised the shoreline. At her feet, sandpipers busily chased false leads. She had come here after the divorce and the ocean and the house had kept her sane.

She sat on the beach, her legs stretched out in front of her. She was proud of her legs; even now she had escaped the river delta veining and cellulite of so many of her friends. Idly, she prodded the skin on her thigh. Scores of tight, parallel wrinkles appeared. Irrelevant though it was, it seemed she was just a finger-prod away from old age, her skin already half a size too large for her body. “Goddamn it,” she cried and went back into the house, slamming the door so hard that the gulls decamped to a spot twenty yards down the beach.

She had been unlucky. Cancer of the womb is not uncommon and curable if caught early. The cancer usually begins in the lining of the uterus, the endometrium, and more often than not, it announces its presence, the most common symptoms being bleeding after menopause or irregular or heavy bleeding during menopause. For Nessa, young at fifty to get this form of cancer, there had been no obvious warning, no red flag of danger. Other symptoms—the abdominal pains and the tightening of her waistband—she had not thought to be significant. Aware that her stomach was distended, she had put it down to aging and overeating. For a year she fought her tumor with low-calorie brownies, a story she told later with dry amusement.

The cancer had been high grade and aggressive and during Nessa’s diet it moved deep into the wall of muscle around the uterus, then into the cervix and the lymph nodes in the pelvis, then on to the cavity of the abdomen before moving north for the lungs. She had endured surgery and regular bouts of chemotherapy, but three years later she knew she was not going to survive. She was out of remission. Her oncologist thought she might live for six months, a year at most.

Tom and Jane knew of her cancer from the beginning. She had sent a cheery, casual letter; it was a nuisance, she wrote, like an arm in plaster, inconvenient, but in time the body would mend itself and soon she would be as right as ever. Jane had replied: “It will be easier if we’re honest, won’t it?” and they had been.

Her cancer and her grandson had announced themselves at roughly the same time and Hal had always been her best kind of therapy. From the start they had been close. So confident and breezy with adults, she spoke at first only in whispers to Hal.

“Everything they have is straight from the store,” she had said to Tom. “It’s all unused, hearing and eyesight 100 percent—we grown-ups should keep the volume turned down.” She was one of those people who instinctively

squat down to talk to small children and there was in her face a regularity they trusted.

Tom and Jane came for a month each spring and for another three weeks every other Christmas. In the summer she would visit Norfolk, staying for the whole of June. The generous month, she called it. A late spring and she was in time to see the froth of cow parsley in the lanes, while early warmth meant the old roses would be blooming in the grand gardens they visited. Whatever the prelude, in June the Norfolk countryside is rich with compensation. She loved this soft bounty and thought often of the garden she and Henry had created in London—apart from Tom, their most successful joint venture.

In Florida, it’s different. What the English call gardening they call maintenance and the less there is of it the better. There are no flowers in Nessa’s garden—she hated the gaudy colors of the busy Lizzies that line every driveway on the Boulevard. Instead, her garden is laid to grass, the tough, springy ryegrass that can survive both sun and salt spray. She had worked hard to preserve the thirty inherited coconut palms that cluster around the house.

The Upright Piano Player

The Upright Piano Player